In the short term, the government will respond harshly and the atmosphere may deteriorate. But in the long term, the dust should settle and reveal an opportunity to further integrate China into the international legal order.

A poster showing a map of China, including Taiwan and the South China Sea, appeared in Weifang on 14 July 2016. Photo via Getty Images.

The award issued by the Arbitral Tribunal in the South China Sea case has been a tremendous blow to China. For years, China maintained a vague and unsustainable claim to unspecified ‘historic rights’ within the zone delineated by the ‘nine-dash line’ encompassing almost the entire South China Sea. It safeguarded its interests by calling for bilateral negotiations in its disputes with the other adjacent states, including the Philippines, and was happy for negotiations towards even a mere Code of Conduct to proceed at a snail’s pace.

The initiation of the arbitration case under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) by the Philippines in September 2013 changed all that. China, caught by surprise by the Philippines’ move and ignoring its own prior consent to compulsory proceedings under UNCLOS, boycotted the proceedings, albeit half-heartedly. Nobody expected the outcome to be positive for China, especially after the tribunal ruled that it had jurisdiction to hear the case. But most observers have been surprised by the extent of the award, which has swept the majority of China’s expansive claims off the board and clarified many unanswered questions about UNCLOS in the process.

The immediate question is whether these findings will have any tangible impact since China will not comply. It could also be argued that the award lacks legitimacy because the integrity of the proceedings has been damaged by China’s non-participation, even if it did make some of its views known through the public record and by informal communications with the tribunal and its members.

With regard to the first question, China’s immediate diplomatic response should be distinguished from its actions in the long term. In the short term, China will roar, and things may get ugly. The Chinese government and its proxies initiated a sustained campaign to discredit the tribunal months before the award, which culminated in some extreme rhetoric in the days immediately following its publication. This included smearing the members of the tribunal, allegations of backhanded US machinations behind the Philippines’ actions and threats of military escalation. These actions seem designed to shore up domestic support and save face against nationalist elements.

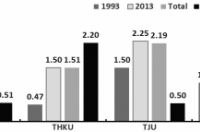

In the long term, however, China should be expected to carefully study the award and come up with a more measured response. China is invested in the international legal order and has no shortage of competent international lawyers, some of whom advised the government to make its case before the tribunal but were ignored. Their advice may be heeded after the shock learning process which the government has been subjected to. China still sees itself as a relative newcomer to international law, lacking experience and confidence with regard to dispute settlement, but it has plenty of experience to draw on. For more than a decade, it has participated in the WTO Dispute Settlement Mechanism, where it has fought 47 cases, often emerging victorious. Just this week, China announced that it will initiate another case.

For all the often-heard scepticism about the relevance of international law, the award now stands and will still stand months and years from now, when the current turmoil will have long been forgotten. With proper Chinese participation, some findings might have turned more in China’s favour. A close reading of the award reveals that the members of the panel went out of their way to take into account China’s position to the limited extent that it could be known.

Eventually, any flaws which may be present in the award can be remedied in negotiations which take the findings of the arbitral tribunal as a starting point. Without ever formally acknowledging the validity of the award, China can make gradual adjustments to its position to accommodate its findings and resolve the underlying sovereignty and other disputes in the South China Sea, which were not addressed by the tribunal.

To benefit from its victory, the Philippines should not gloat (and has not so far) but present the award as a public service to all countries adjacent to the South China Sea, as it may well turn out to be. The clarifications to UNCLOS made in Philippines v China may well turn it into a leading case, much like another case in which a great power stayed away, when the United States withdrew from the Nicaragua case before the International Court of Justice in the 1980s after losing on jurisdiction.

For now, the tribunal’s findings will cause pain in China, but it may also contribute to China’s further integration into the international legal order.