The 13th Five Year Plan will not only shape patterns of global development, but also help determine the fate of the environment.

Solar panels in Xuzhou. Photo via Getty Images.

Much of the focus on China’s 13th Five Year Plan – its centralized and integrated economic guidelines for the next five years – has been on the estimated growth rate of 6.5 per cent, its lowest in recent history. This reflects the so-called ‘new normal’ of China’s development, as President Xi Jinping’s administration describes its aspiration for higher-quality growth in the context of a slowing economy.

But this growth target is an estimate, rather than a pledge. The emphasis on ‘ecological civilization’ – another of Xi’s signature buzzwords, referring to a broad set of approaches environmental protection – is striking. Further, by putting innovation and ‘green development’ at the heart of its ambition to create a ‘moderately prosperous society’, China has sent an important signal: that the country’s strategy for future prosperity in many respects converges with a shift away from its environmentally costly development model.

Environmental goals

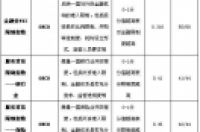

The plan endorses a ‘vertical management system’ that will help overcome structural impediments to the local enforcement of environmental laws, and of its 13 binding targets, 10 relate to the environment and natural resources. In the plan, China commits to an 18 per cent reduction in carbon emissions per unit of GDP from 2015 levels by 2020 and a 15 per cent reduction in energy consumed per unit of GDP from 2015 levels by 2020. It also re-commits to generate 15 per cent of primary energy from non-fossil sources and introduces an important new target of keeping energy consumption below 5 billion tonnes of standard coal equivalent by 2020. Underlining how air quality has become a major driver of energy and climate policymaking, it also promises a 25 per cent reduction in harmful PM2.5 particulates.

In short, the plan suggests that decision makers in China not only take seriously its UN pledge to see a peak in the country’s emissions before 2030, but also that they hope the country will be the leading supplier of low-carbon technologies. Among its non-binding targets are some significant innovation-related measures: to raise gross expenditure on research and development as a percentage of GDP to 2.5 per cent, from 2.1 per cent today; and over the same period to almost double the number of patents owned per 10,000 people, from 6.3 to 12.

Innovation

The document makes clear the principal driver of China’s economy should be innovation, rather than investment. Innovation, says the plan, ‘must be placed at the heart of overall national development’ and ‘integrated into all the works of the Party and the country’. There is emphasis on strategic areas at the ‘frontiers’ of science, ‘mass entrepreneurship’ through new models such as crowd-funding, and digital economy projects – what the leadership likes to call ‘Internet+’ – including around the Internet of Things, quantum computing and big data.

Under China’s 12th Five Year Plan (from 2011 to 2015), the state focused on a defined number of specific technology goals in its ‘strategic emerging industries’. Renewable energies and electric vehicles, for example, were afforded specific preferential policies. By contrast, the new plan has a greater focus on ‘clean coal’ and hydropower in the energy sector; and while it doesn’t abandon solar and wind, it also suggests greater diversity in its overall approach, with more of an emphasis on reform of the energy sector, developing smart power grids and investing in energy storage technologies such as batteries and fuel cells.

Moreover, innovation in the plan is not framed as simply being about hardware – the commercialization of science and technology. Rather, the text reiterates that innovation should come in many different varieties: ‘theoretical, institutional, scientific and technological, and cultural innovation’. This raises the intriguing and hopeful possibility that the country’s planners recognize some of the challenges and opportunities the public, particularly in the form of newly vocal, engaged and connected urban constituencies, pose in the governance of innovation.

Policymakers – taking ‘social innovation’ seriously – could begin look at the public as technology users, incubators of demand-driven successes, and innovators in their own right. In a context of low public trust around food and agriculture in China, for example, organic cooperatives and ecological entrepreneurs have pioneered supply-chain innovations, typically facilitated by digital networks, to connect farmers with urban consumers looking for safer food. Lower-tech approaches to energy too – such as inexpensive solar water heaters, which garner a mention in the latest plan – have been driven by rural users and supported by local initiatives, rather than central government coordination or subsidies.

These approaches to innovation would present a quite different model than previous central government plans have encouraged. Whether in the plan’s implementation they are harnessed and given support might be critical to meeting China’s environmental goals, as well as its drive to create a more innovative economy and society.